Midnight on the lake

No wind, no waves

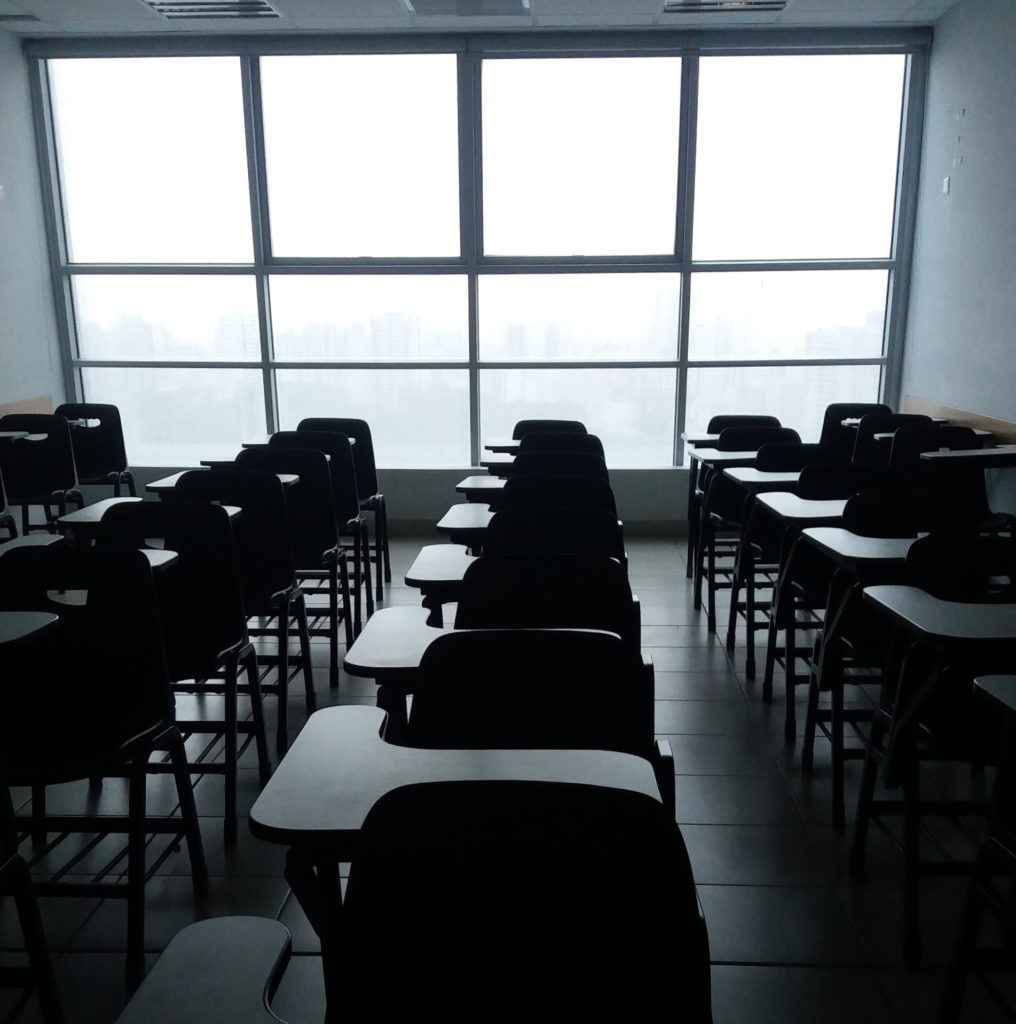

the empty boat

is flooded with moonlight.

—Dogen Zenji

It has been quiet over here for a long time. There is great comfort in deep silence amid the cries of our suffering world.

Silence doesn’t have a meaning but we often project a meaning onto it. We might think, for instance, that silence implies anger, offense, or indifference, but that is not always true. What is true is that silence and stillness abide eternally in our very being, when the winds of emotion have calmed and the waves of thought have ceased. Then we might have something useful to say. Or not. Sometimes silence says it all.

The other night I gave a talk on forgiveness. It came to mind because of things in my own life and most certainly because of the cruelty, injustice, and inhumanity in our world. We need forgiveness, and we need the humility to give it, because forgiveness is the best remedy for anger and resentment. It allows a new beginning.

But forgiveness is a rather sticky business. Anger is an intoxicant, and intoxicants are addictive. If we look at ourselves closely, we may see that we hold onto our anger, grievance, and blame. They give us—what, really? A sense of self, perhaps. Purpose. Certainly a sense of self-righteousness. Letting go takes the strength and discipline to get over yourself. You have to really want to get rid of the pain.

Years ago someone asked me a particularly good question. They asked how this practice changed the way I dealt with conflict. All high-mindedness aside, how does it make a day-to-day difference? I didn’t give a long answer, I just said that I’d learned to pause in the face of conflict so that I didn’t immediately react to anger with anger. I could still respond, but it was more often with silence. Or an apology. It’s a lot of trouble to win an argument but there’s always a way to end it.

The talk was given on a night when our sangha observed the ceremony of atonement, called Fusatsu, which conveys complete acceptance of one another and total responsibility for the harm we cause. No excuses, no blame, no wind, no waves, no self. It returns us to the silence of a night sky, the stillness of calm water, and the radiant light that shines in us, when we empty ourselves out.

You can listen to the talk right here. Or here. Or not listen, and just enter the silence.