Where do we go from here?

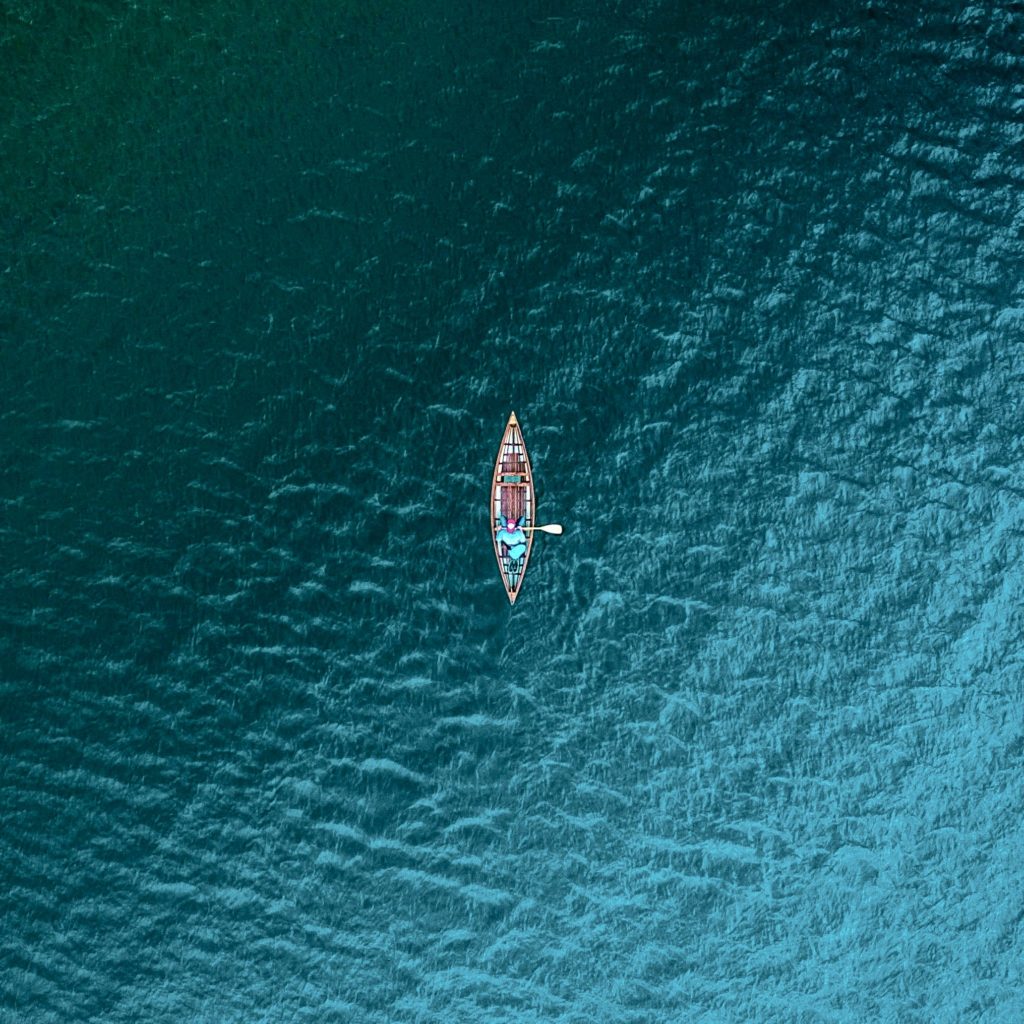

I went for a walk today. I was going to type, “I went for a long walk today.” That was what I announced before I went: I’m going for a long walk today, the way I would have said it the day before yesterday or last week or last month. In the days before yesterday if I went for a walk it was to accomplish something, get my steps in, the 10,000 that would set off the Fitbit buzz on my left arm, so I could feel good about what I’d done.

But today I went for a walk just to walk, because at this point I don’t have a scheme or a fix, a goal or a get. After long-pondering which way is forward, I know that the only way forward is forward. It always leads somewhere new.

It’s really that simple, but it’s sad, too, because the world is so very fucked up right now. Who can even picture what comes after?

In the old days when I had a dog and wrote books, I’d be muddling over a metaphor in the middle of the day when my pup would put her lovely head on my lap and wiggle her butt, the sign that it was time for a walk, which always seemed like the worst possible time to go for a walk, but I would give in and take the walk around the block that took all of 15 minutes and come back and realize that the muddle in my mind was gone. I was freed from the word trap that paralyzes a writer trying too hard, which I usually was. Trying too hard to say something.

And so I set out today and the air was cool but the sun was warm, and I saw that Christmas decorations are still up, poinsettias on porches, icicle lights along the eaves, and then I remembered that it is still just the first week of January although the weeks are years and the years are eternities, and I am so very tired.

The other day someone who sits with our Zoom group said that I look like I have the weight of the world on my shoulders. In the truest sense I do have the world on my shoulders—we all do—and as for the weight, I wondered aloud, I did have my very unhappy daughter home for half the year, because COVID came and her life collapsed, and the relentless fires, my husband’s surgery and its setbacks, the sickness upon sickness that is American life and politics, the panic, the fear, the dread, the death. Yeah that. And now this.

I hadn’t walked too far across town when I came to the middle school, the site of so much preteen pain. I crossed the street for a closer look when I saw an art display fastened to the fence at the front of the school. They’d had a themed art contest, perhaps for Thanksgiving, with students making posters illustrating gratitude for someone or something in this desolate year.

Thank you, Dodgers! said one, because let’s not forget the first World Series win in 32 years, although two months later that seems oddly quaint and woefully irrelevant.

Thank you, Essential Workers! Those are words we won’t soon be able to forget, even though I’m not completely sure what they mean. I have a friend who works at a plant where herbicide is made and she is considered an essential worker, putting in 80-hour weeks with no time off, risking her health for the urgent purpose of killing weeds till kingdom come. But, yes, we can hardly express enough gratitude for doctors and nurses and teachers, grocery clerks, transit workers, the postal service and delivery drivers. On the last leg of my walk I passed a driver picking up waste from a portable toilet, and the stink radiating from his vehicle made me realize how very unsung his essential work must be.

Thank you, First Responders! Thank you, Firefighters! California was incinerated this year, despite Trump’s imbecilic advice to rake the forests. No thank you, Sir.

There were tributes to Black Lives Matter and Greta Thunberg, lifting my hopes that middle-schoolers could well save the world or at least never stop trying.

There was one poster among all of them that stood out and stayed with me on the walk home, because this is what I’m most depending on for the survival of my soul and sanity. Thank you, Joe and Kamala! For taking the lead on what will be a very long walk to a very distant day when we can once again sit back and feel good about what we’ve done. And while I’m at it, thank you Raphael and Jon! Merrick, Xavier, Miguel, Pete, Janet, Deb, Alejandro, Marcia, Antony, Jennifer, Lloyd, Tom, Denis, Gina, Marty, Isabel and Don. With you good people at work and in charge, I can walk off the weight of a world nearly destroyed by a vulgar and traitorous despot. I’m not counting the steps or the days or the years. I have complete faith in the direction we’re heading, because the only way forward is forward.

May it be so.

Photo by Rosie Kerr on Unsplash