Open to everyone

Marillac Center Retreat

March 20-23, 2025

Marillac Retreat Center

Leavenworth KS

Registration open

Open to everyone

Marillac Center Retreat

March 20-23, 2025

Marillac Retreat Center

Leavenworth KS

Registration open

Having entered this world, now exit it completely. This house is not a place for staying long. — Rinzai

It is a time of transitions. It is that time for all of us, all of the time. Time to let go of what we have held onto. Sometimes the things we hold onto are ideas — hopes, dreams, and expectations for ourselves and others. Sometimes they are the things and people we love. And sometimes what we cling to are beliefs about ourselves: who and what we are. These are hard things to let go of. We don’t want to see the reality of change and the truth of impermanence.

But sooner or later we’re going to come up against this thing that most of us are avoiding or denying: the great matter of death. The intimate experience of impermanence. The Dalai Lama calls awareness of death the very bedrock of the path.

This is a timely issue for me and many of you. My teacher has just died. For some of you, your parents are sick or dying. Your cherished pets have died. Or perhaps we ourselves are increasingly aware of how much shorter our own horizon is. I know I am. In a way, it seems to happen in an instant. A 60-year instant or a 70-year instant, and overnight, we are old. Of that my daughter is so afraid, so she insists, “Mom, you’re not old! Promise me you will live to be 120!”

But I am not afraid, because I know: this house is not a place for staying long.

My mother died many years ago. She was sick with a disease that had mutilated her body. Her death was not a shock or surprise. It was a clear and merciful blessing. What shocked me was not the finality of her death on that day, it was the presence of my life. Life flowing, life ongoing. It seems like a sacrilege to go to the supermarket on the day your mother dies, but there was no other alternative. There was nothing other than that for me to do.

When someone you know has died, you are instantly returned to your ordinary, everyday life, which may seem quite mundane. But that is in fact your awakening: to take care of what is right in front of you, when it is in front of you. Drinking tea, making dinner. That’s it. To see the life, your life, moving and flowing from one moment to the next, and carrying nothing with it.

I have just given a talk on this topic, “The Dharma of Life and Death.” You can listen to it at this link.

Maezumi Roshi often started a talk by saying, “I just want to encourage you.”

This at a time when we had endless cause for disappointment. We always have endless cause for disappointment, don’t we?

But around that time we had earthquakes, big earthquakes, riots, deadly riots, we had the karma of Vietnam, Nixon, and Reagan. We had protests where the national guard shot and killed college students. We had the cold war, the nuclear arms race, we had oil embargoes, we had the Iran hostages, we had so many assassinations, so very many assassinations.

The world is a crumbling place.

But I want to encourage you. Encourage you to do what? Just keep going. Face reality. Stay present. Love one another. Do the next thing. Stay awake. Stay aware.

This awareness is what you are, what you really are, what we sustain and maintain. Even when you feel most unmoored, uncomfortable and afraid, beneath it all is this awareness, this presence, that is your wisdom and your refuge.

I know that many of you, like me, gave a lot to this election. Money, time, faith, hope, optimism, even certainty, however false. And now we feel empty. Bereft. Even betrayed, with nothing more to give. But there is something we can give, and it’s the fruit of our practice.

As a standard of giving, we say that the best thing to give is no-fear. No fear is infinite compassion. Compassion is not sympathy or pity. It is feeling the pain and feeling the fear of another. How do we do this? When we don’t have our self-centered ideas, worries, doubts, judgments, what-ifs, and what-thens, then what we give is no-fear. There is nothing more important for us to give right now than that.

A student asked a great teacher, “I am very discouraged. What should I do?”

The teacher answered, “Encourage others.”

This message is from a dharma talk I gave last week. You can listen to it at this link. I offer it to you as encouragement, and by accepting this gift, you encourage me. That’s how this works. That’s the only way any of this works.

Last week I met with a friend on Zoom. The caller said that she didn’t have anything in particular to talk about, but that she just wanted to keep the connection between us. I applauded her. Connection, you might say, is everything.

But you know as well as I do: these days we’ve got connection all wrong. With phones, email, texting, DMs; meeting apps instead of meetings; patient portals instead of doctor’s offices; social media instead of social, well, anything. With instant online shopping and banking; remote working and remote schooling, and so on, and so on. We can’t even list all the ways we have co-opted and confused real-life human connection. Even a connection on Zoom isn’t a connection, although it’s often the only connection we have.

When my friend and I were talking I remembered a line that someone famous had once said, a screaming, crying, urgent exhortation to remedy modern life: “Only connect!” Was it Buddha? Jesus? Oprah? I looked it up.

It wasn’t so modern. It wasn’t so holy. It was the author E. M. Forster in his 1910 novel Howard’s End.

“Only connect! Only connect the prose and the passion, and both will be exalted, and human love will be seen at its height.”

He was writing about relationships, and the social strictures that keep people distanced. That breed fear and loneliness, that stifle communication and kindness. For all our snazzy inventions, for all our lofty intentions, and against our basic need to meet, gather, herd, commingle, and yes, connect, we have only succeeded in driving each other further apart.

But rarely, I get a glimpse. I get a glimpse when I see a delivery person walking up to my door. Up to my door! And the knock. Will I open it, or will I pretend I’m not home? Will I say hello? Will I say thank you?

I get a glimpse when I’m in a room with other people. It may be a big room, or a small one, no bigger than my front porch. It may be a quiet room, or it may be a noisy room. It may be with people I know, but more often with people I don’t. It’s not likely to be people who think like me; more often it’s probably not. There may be talking, there may be singing, there may be silence, there may be stillness, there may be dance. I feel it in a theatre, I feel it in a stadium, I feel it in a grocery line. It’s in a meditation hall or church, in a hospital waiting room, at the post office, and with total strangers in the airport shuttle. It’s on my street. It’s on your street.

It’s the people, the people, the people! And the invisible, unknowable essence that flows between us, that unites us and defines us, not as separate, but as whole. That’s our beauty! That’s our power! That’s the height of our existence, revealed when we only connect.

I’m hopeful. I’m much more hopeful.

Photo by Keith Luke on Unsplash

One night’s lodging brings rest to the body; two nights give peace to the heart; after three nights the drooping and depressed no longer know either trouble. If one asked the reason, the answer is simply—the place. —Po Chu-i (772-864)

One night’s lodging brings rest to the body; two nights give peace to the heart; after three nights the drooping and depressed no longer know either trouble. If one asked the reason, the answer is simply—the place. —Po Chu-i (772-864)

Chapin Mill Retreat

Oct. 10-13, 2024

Chapin Mill Retreat Center

Batavia NY

Registration open

All are welcome

I visited Washington DC a few weeks ago. It was 100 degrees; the grand boulevards were all but empty. I walked a merciless mile through patches of shade to the National Portrait Gallery. I’d never been. I’m not sure I will go back or that it will still be there if I do. What will become of this place and its people when all is said and done?

These days we hear a lot of racket about our founding fathers and their original intentions. We hear mostly from people who interpret our history and constitution, indeed all our laws, by the notion that they, and they alone, uphold the narrow meaning of the 4,500 words on the four pages of a 240-year-old document, written in secret and signed by 39 white men.

When I entered the gallery, I didn’t know what was inside. For sure, I wanted to see the presidential portraits, especially those prized for their artistry and originality. I wanted to see them with my own eyes, I suppose, to restore my sagging spirits.

You begin by parading past portraits of colonial, revolutionary and early Americans. Sadly, these do not restore your spirits, because these are portraits of the vain and, mostly, vile. Men who might have escaped crimes or debts to amass or inherit a princely purse. Moneyed men who possessed vast reaches of stolen land, once taken by massacre or manipulation, from which profits were extracted by hundreds if not thousands of slaves. There are room after room of them, generations and venerations of them. I’m no constitutional scholar, but the meaning was clear.

When they wrote “we the people,” they could not have meant people like us. They meant only themselves, because only they enjoyed the inalienable rights of personhood.

When they wrote of freedom, they could not have meant us, only that they themselves were free, and that their freedom was not challenged, but endowed at birth.

When they wrote of equality, they meant only that among themselves they were equal in power, place, and participation in this closed society.

They had thrown off the yoke of a king to make themselves kings. The expansion of rights, freedoms, and equality were granted to the rest of us much later on, only to be taken away at whim. It’s no wonder that we’ve been steered here again.

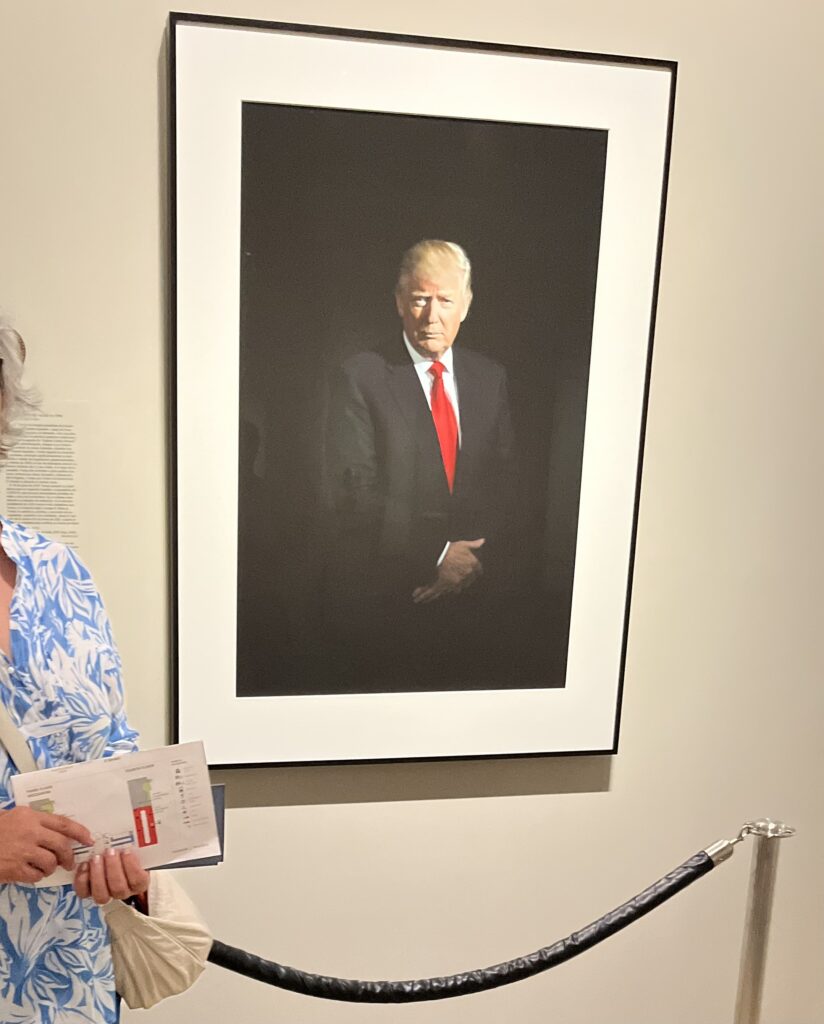

There is a political and philosophical through-line from the first-floor galleries to the far corner of the second floor where the hall of presidents comes to a stop. It ends with another picture of outsized greed and vanity, a slenderizing photograph of Trump veiled in darkness, posing in Churchillian pretense, draped in a blood-red tie. It is located on the backside of the gloriously colorful portrait of President Obama by Kehinde Wiley. When I stepped around the edge of the display to glimpse Trump’s image, I was afraid to see who might be standing there admiring it.

But the woman I encountered, off to the side, was like me. She was afraid, but not of me. She was proud, but not of him. We said these things to one another in secret, without betraying the other, because we know we are not free, we are not considered equal, and more than any other time in our innocent allegiance, we are not safe in this country.

But we have each other. And we parted knowing that we are not alone.

My husband and I have been trying to muster the wherewithal to update our will and advance healthcare directives. Twenty-odd years ago, we sat down with an attorney friend and in one evening had the whole thing knocked out. That’s probably because we felt like we were still in the middle of life, where time seems suspended. That can happen with a young marriage, a new home, and a small child. The future was far off, and events that would happen there were just a fuzzy abstraction.

Not so now, for obvious reasons. Not so now at all.

Sometime in the last year my Zen teacher, who is a good twenty years older and infinitely wiser than I am, gave me new instructions for my meditation practice. “Keep your gaze focused on the horizon.” For me, this involved lifting my sights higher off the ground than I’d been used to. And at once, my view expanded and the horizon came closer. I likened the change to watching a sunset on the beach: we can’t take our eyes off of it. It’s instantly relaxing, absorbing, and quieting. Don’t we savor a sunset? The delicious array of color as the light scatters. A subtle cooling in the air. The slow encompassing of darkness. The indescribable beauty, the inexplicable magic, the doneness of it all.

That’s how I see my horizon now. As it shortens, it beckons as a raft to ride beyond the rising swell. I am less afraid of what lies over the edge of time. Trust me, I’m not hasty to leave. There is so much to do right now. I can’t hope to change the tragic and horrible course of ignoble human events, today in this country, in this world, borne of the deepest evil, hatred, greed, and insatiable corruption. But I will try. I will show up. I will support. I will give comfort and care. I will hold fast to goodness, kindness, gentleness, charity and love, as we must, bravely. My time is short, or shorter than it was — a comfort of sorts — but there is not a day to waste. There is not a day that doesn’t matter.

Photo by Jorge Fernández Salas on Unsplash

When I was 16, I got a chair for my birthday.

It was a little wicker chair from Pier 1. Nothing about it seems unusual to me now except that I asked for it. Who asks for a chair for their birthday? Perhaps I was trying to piece together a different kind of life than the one I had. My room was already too small for the furniture in it. You had to walk sideways to squeeze between the bed and bureau. Maybe I used that chair to hold clothes or homework. I can’t remember much about it, except that it was mine, and that mattered to me then.

I took the chair with me into all the places I lived over the next 20 years. As those places got bigger, I’d tuck it into a corner, a closet or a spare room. The kind of room you never walked into. Over time, the little chair became not so much a chair as a sentiment, a feeling about the past. I never sat in it at all.

At some point along the way, I needed to move out of a big place and into a smaller one, a really smaller one, not much bigger than my bedroom was when I was 16. It was time to let go of everything—furniture, dishes, clothes, yard tools, rugs, books, the assemblage of a lifetime—and I did, ending with a garage sale one Saturday morning when I put the little wicker chair out on the lawn. No one seemed to notice.

Almost everything was gone by the time a fellow rode up on a bike. He bought the chair, marked down from $10 to $5 to $3. Then he rode off one-handed on his bicycle, carrying the chair over his back.

I was so happy. I was happy for the man, who didn’t have much. But mostly, I was happy for the chair, because I knew someone would soon be sitting in it. It would be a chair again, and not just the memory of a chair.

I don’t know what might have caused my sister and me to be riding in the back of our ’57 Chevrolet, the light green sedan that my dad would drive for many more years. I don’t know how or where we found ourselves motoring slowly through a flooded street, water lapping in waves, into the dark ahead. I was afraid, that much I remember.

We pulled into a gas station. Was it so my dad could call my mom on the pay phone? We would be late. She would be worried. Was it to buy cigarettes or a beer? To ask for directions? Were we lost? Were we stuck? Would we make it? We didn’t say any of these things out loud. Inside the car, we didn’t move. Maybe we were told to sleep, and maybe we pretended we were.

When the rain is heavy the wipers don’t clear the windshield for long. You have to drive through the blindness until the blur is wiped away again. Seeing, not seeing, knowing, not knowing. You can learn this from the backseat on a rainy night, even if you’re only four or five.

Was this the first time I was truly afraid? Is that why I remember it? It would not be the last. There are so many ways to be afraid, and afraid even after. I am still afraid riding in a car. A curve taken too fast. The brake coming too slow. A foot on the pedal, faster, faster. Where are we going and why are we going like this?

I don’t say anything out loud.

My father got us home that night. That night he was a hero, a giant to little me. I should remember that. I should remember being safe, being carried home.

There are so many ways to be afraid, and only one way not to be afraid. By trusting what you can’t see. Going where you don’t know. Still and quiet in your seat, as the waves come and go.

Women’s stories are hard to believe. And they are hard to tell. They don’t fit the narrative, someone will tell you. They are called exaggerated, overemotional, irrational, and unbelievable. Women’s stories are often horror stories. They terrify us because we realize how vulnerable and powerless women are.

The other day I watched the documentary American Nightmare on TV. It was a story you couldn’t turn away from, although many had.

A man and woman are attacked in their bed in the middle of the night by a masked intruder. The man is knocked out while the woman is drugged and kidnapped. She spends hours tied up and blindfolded in the trunk of a car, then days being assaulted in a blacked-out room.

The police never go looking for her because they don’t believe the story the man tells about what happened. It doesn’t fit the narrative.

When her captor releases her, the police don’t believe her either. They don’t even listen. They’ve already decided it’s a hoax, and that makes her the criminal. Is the nightmare what happened to her that fateful night or what happened to her after?

When my daughter was in college she made friends who were student filmmakers, among them, women filmmakers. Some made films with crews comprised entirely of women: actors, writers, directors, producers, camera operators, editors. These women came together to tell women’s stories, the stories that most often don’t get told. Now she and her friends are trying to tell one such story in a short film entitled There’s Someone at the Door. It’s about how two women respond to the possibility that danger is lurking in the dark. This is a fear that can be present everywhere, everyday, especially in the lives of women.

The artists involved are raising money for the film. They have a far-off goal, but they will make the film anyway, somehow. Perhaps you can help these women tell the story, even in a small way. (At Indiegogo, click the red button that reads “See Options.) What matters most is that someone believes in them.

Thank you.

The other week I went to my bank’s ATM to make a withdrawal and it wasn’t working. I turned around and left to try again the next day. When I came back, the ATM still wasn’t working. It felt kind of weird, but I went inside the bank.

I mean, who goes inside a bank anymore? For that matter, who needs cash? Just the people who do things like me, I suppose.

There was only one person inside, a teller. There were empty desks and chairs where you might have sat if you’d been opening an account, applying for a loan, or purchasing a CD in the old days, but this one fellow was it. He was the whole bank.

The ATM isn’t working, I said. I felt like I should explain my presence.

I’ve heard that, he said.

He counted out the bills and I left. He was alone again.

I’ve thought about this since. I think about all the ways our world is different now, lonelier now, disconnected and isolated, and what the future will hold for the kids who don’t know any other kind of life. By that I mean a life with people that you meet and talk to, that you rely on, and that you trust in an everyday kind of way, even if you’re strangers.

A long time ago, in the ‘70s and ‘80s, there was quite a bit of controversy over something called a “neutron bomb.” It was considered especially efficient by the military-industrial types because it would kill people but leave (most) buildings intact. Reagan initiated production of the bomb but anti-nuclear protests put an end to it. The bombs were never used and the ones they made were dismantled.

But it feels like the aftermath of a neutron bomb anyway. Like the people are gone and an empty world remains.

Are you OK? Does anyone ever ask you that question for real, in person, in front of you?

As for me, I don’t encounter many people anymore. Oh, there are people most places but I don’t really encounter them. There’s a woman who works in the self-checkout area at the supermarket and I see her most days when I’m there. We recognize each other, smile and chit-chat. That counts as a pretty big deal.

Before the pandemic, I used to drive to a yoga class every other day and see the same people on a certain corner. If the light turned red and I was stopped, I would roll down my window and hand whoever was there a $1 bill. In those days, I always had at least a few $1 bills. They’d say thanks or bless you or have a great day and I’d smile. Sometimes, we’d even exchange names. That was what you called an encounter.

One day it was pouring rain and the corner was empty. I drove on through several more intersections until a light turned red. There was someone with a sign, someone I’d never seen before, but I had a $1 bill ready and I rolled down the window and gave it to him. He stooped down to see me through the open window, me with my head nearly as bald as a sick person’s, and he stepped closer, squinting.

Are you OK? he said. He was soaking wet without even an umbrella, let alone a home, and he was worried about me?

I had a clutch in my throat then, and I do now. I don’t think I changed his life, but he changed mine.

Are you OK? Are you OK? Are you OK?

###

Photo by Frames For Your Heart on Unsplash

The other day I drove down the hill and into a fog bank. A fog bank, yes, out of the blue. The weather is so odd around here — cloudy, gray, foggy— strange for September, which has always been our hottest month of the year. But that was then.

Just about all weather is strange these days, but ours is a stranger-than-ever world. It’s hard most days to lift one’s sights above the gloomy prospects.

It makes me think of this photo. It was taken at a children’s playground where underground misters emit a continuous flow of fog. It’s an ingenious form of play, and the kids can’t get enough of it. Without seeing farther ahead than their feet, they run and jump and get wet, but amazingly, they don’t get hurt.

I’m guessing she was about six years old here, because I don’t think she could have struck this pose after that. After this, she would have known a lot more. She would’ve known, for instance, what she couldn’t do, or shouldn’t do, what she was good or not good at, what other people liked or didn’t like about her, who said what, what things meant, and all of that, all of that. To her then, this pose wasn’t a pose. In this moment, emerging from the mist, confident, happy, and free. Pointing at me as if to say, even now, can you do this? Forget where you’ve been. Don’t think should or could. Without knowing what lies ahead, isn’t this everything right here?

Many years ago, when my life seemed to take a radical and inexplicable turn, people would sometimes ask how I decided to make that happen. The truth is, I didn’t make anything happen except in the smallest ways. I didn’t decide to downsize, for instance, although it looked that way. I didn’t become a minimalist, although my needs diminished. I didn’t decide to pursue a spiritual path, I just put one foot in front of the other. I didn’t resist, reject, or refuse anything, I simply made different choices. They are the kind of choices we are presented with all the time.

Instead of more I chose less. Instead of that I chose this. Instead of later I chose now. And instead of me, well, I didn’t choose me.

If we are lucky, we are given a great deal of time on this earth, time enough to get a good look around. And eventually, after enough upheavals, disasters, and disappointments, we might realize the point of it all.

It’s not just to be kind, although that’s part of it. It’s not just to be tolerant or generous, although both of those will become easier. It’s not really about gratitude either, although you will be grateful for all the opportunities given to you.

We are here, together, now to serve one another. Let’s not make that complicated. It’s really simple, and a lot simpler than serving yourself. Serving yourself is an endless, exhausting, and futile endeavor. It perpetuates dissatisfaction. It multiplies desires. But serving others, helping others, and caring for others is a tiny, weightless thing. It’s instantly satisfying and gratifying. In other words, it’s good.

This is the secret to happiness. Let’s not keep it a secret.

Become the least grain of sand at the beach.