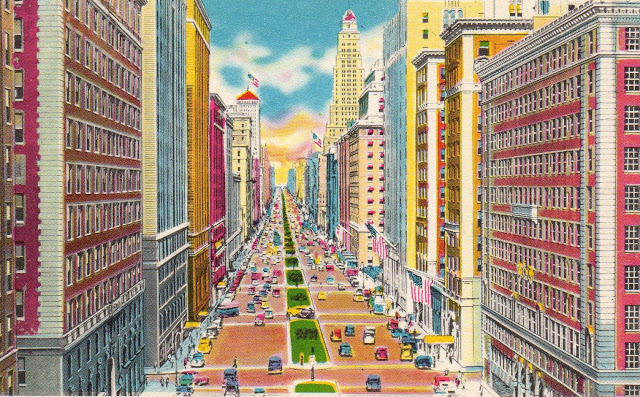

The Tiffany Building, New York

When you die can I have your jewelry?

My daughter must have been 7 or 8 years old when she said this. It was one of those bugle calls our children regularly give us without guile or guilt. You are old and going to die! At other times, she asked for certain fancy dresses and pointy shoes post-mortem. I took it as a thief’s form of approval.

When I was in my twenties, my apartment was burglarized. A pair of professionals had watched me leave for work. I didn’t think I owned anything that was worth stealing, but was nonetheless relieved of an old television, spare change, a modest stock of jewelry and all the prescriptions in the medicine cabinet. When the police came I noticed that two silk flower arrangements were missing. Silk flowers were a thing in the early ’80s, but I didn’t believe anyone could fetch a dime for a handful of fake flowers. The policeman set me straight.

Those are for their wives.

I was being crafty when I handed my daughter a trash bag one morning last week, saying if you throw out your old makeup, bath, and hair stuff I will give you my jewelry. I wanted a clean bathroom, you see, and it worked. When she reported back, the duty done, I took a step ladder to the closet shelves and brought a dozen or more little boxes down from the farther reaches where they’d been forgotten. We opened them one by one.

There were iconic robin’s egg blue boxes, dainty ring boxes and long black bracelet boxes, a Baccarat crystal necklace, a box each from Barney’s New York and the Met, and a collection of treasures from a certain antique jewelry purveyor on East 57th. I told my daughter I once had a wealthy admirer who shopped for me whenever he was in the very city which is now her city. Shown the evidence, her eyes widened in appreciation.

Victorian Period

Fifteen Karat Gold Brooch

Made in England

Circa 1880

There were a few souvenirs from my first marriage during a decade when the size of my hair, shoulder pads, shoes and rings coalesced in New Jersey mobster chic. I took out a dusty Rolex watch, a rope of black pearls, and a chunky choker in blazing gold. My daughter demurred.

Some things are too fabulous even for me.

She made an exception for the watch.

After all that, I opened the little wooden jewelry box that I’d kept my wearables in, cheap jewelry chosen by me and not someone adorning me. Most of the clasps were broken. These really were valuables. I’d worn out the stuff. There was one last bracelet rimmed with miniature charms: a statue, a building, a bridge, all the landmarks of Manhattan. I’d once loved it for holding the promise of a new life, a world yet unseen. My daughter claimed it.

I wish I’d known you then.

She said, as if there was ever a single moment separating us.

***

“You may suppose that time is only passing away, and not understand that time never arrives.” – Dogen Zenji

Photo by Benjamin Jopen on Unsplash