Sharing the good stuff all over again.

It was close to 7 p.m., pitch dark and cold by California standards, and I was stopped at a red light on the way to pick up my daughter from math tutoring. The light was long and I let my gaze drift to my left, across the street, where I watched two men waiting for the bus. One wore shorts, the other jeans, both in dark hoodies. I knew they were strangers because they stood apart and ignored each other. In the same moment, each raised a cigarette to their lips, an orchestrated pair invisibly attuned. And then the traffic moved.

Earlier that evening my daughter asked me how we used to Christmas shop. “When you were little did you order from magazines?” she asked, stretching her imagination to conceive of a life without computers. For Hanukkah she was given money and the same day spent most of it on Christmas gifts for friends. The spree had made her happy and it had made me happy too, being much more fun than my grumpy sermons on generosity. She ordered everything online (with my help) and the UPS man delivered the first box today. She went to the front gate and took it from him. I think that was a first, too.

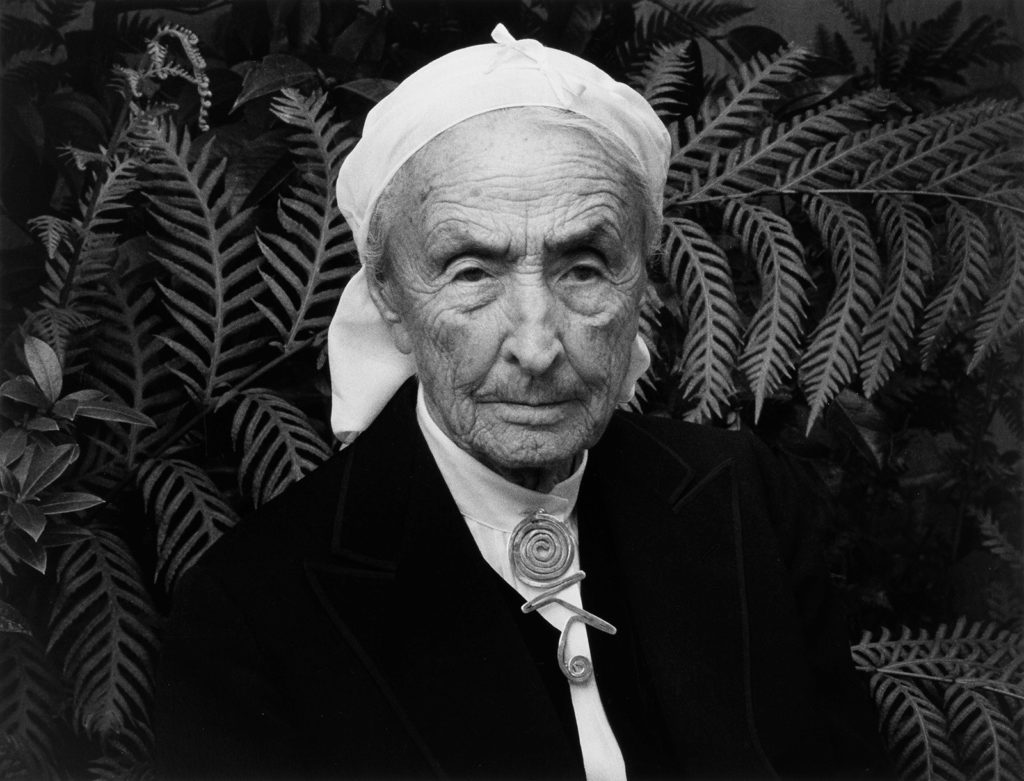

I told her about my grandparents, who seemed crazy rich to us but crazy poor to everyone else. There was a book in those days called the wish book that was really the Sears catalogue. Since my grandparents lived far away from a department store they waited for the wish book to come every year. Then they handed it by turns to three little granddaughters and told us to make a mark by anything we wanted. I’m serious. That’s what they said, and then they went in the other room. It was a big book and a tall order for us little girls, but knowing that I could have it all made me less greedy. I remember pausing my pen over a page, empowered with a Midas touch, thinking of my grandparents, and not wanting quite so much as I thought I did.

Last weekend we saw A Christmas Carol at a local theatre. My daughter was in four such productions since the age of 8, so I have seen and heard Mr. Dickens’ tale brought to life dozens of times. On Saturday I saw it and cried again. I cried because you cannot receive that story and not have it tenderize your heart. There can’t be one of us who isn’t afflicted by anger, frustration, cynicism or a shitty mood around the holidays. There isn’t one of us who isn’t sometimes blind to goodness or stingy with sentiment; who isn’t isolated or afraid. To see a human being transformed by joy, generosity, and belonging — and to feel it for myself — I don’t want anything else just now.

When people say they like the work I am sharing, I look around for the work. This doesn’t feel like work. It feels like life, which is inseparably shared by all of us. If you’re not sure you have anything to share, I will understand. I feel like that sometimes, too. Then I see differently, and my heart is bared. There is good in this world. We have to see it to share it. To start, take a look right here: The Week in Good News.