Let’s consider whether we see a crescent moon, a half moon or a full moon. In any of the phases of the moon before it is full, is anything truly lacking? — Maezumi Roshi

One day a girl looked up at the sky through a veil of clouds and saw that half the moon was missing.

The moon is missing! The moon is missing! No one could convince her otherwise. In fact, she had seen it shrinking for some time, and every night came more proof of her worst fears.

I was right! I’m always right! This conviction was a miserable consolation.

Where others might have seen a sliver of shine, all she saw was the deepening hollow of absence.

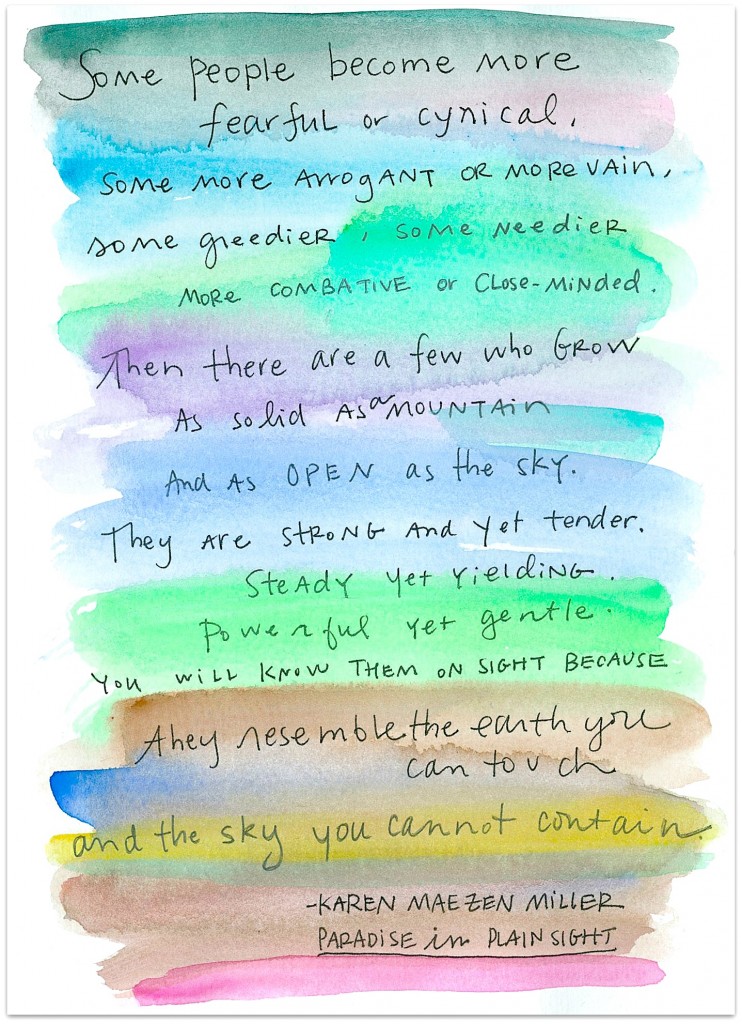

There is something you think you don’t have. A virtue, quality, or substance you need to acquire. Courage. Patience. Love. R-E-S-P-E-C-T! As soon as I name it, you see it as missing from you, quick to disavow the suggestion that you have everything already.

I’m only human, you might say. I’m not at all whole and perfect. I’m injured, inadequate, unappreciated, and yes, even a little bit robbed. Especially robbed.

She tried filling the hole with tears, shouts and bluster. She bought a $429 gourmet toaster with a red knob, a Sub Zero, and a Mercedes, make that a Tesla, piles and piles of shiny, meaningless, objects. They overflowed her house and storage unit, then filled a giant cargo ship that got stuck in the Suez Canal. She stomped her feet and screamed, sent mean emails and angry subtweets. All of it made a mess, but nothing ever satisfied. You can’t fill a hole that doesn’t exist.

And so, exhausted, she gave up and sat down, head heavy, heart leaden.

She didn’t notice the shadows shifting into light, the wind lifting, the clouds parting, the days passing. One evening she opened her eyes and saw the moon. It was full, of course. It was full all along, doing what moons do, reflecting light. Only our perspective changes. We rob ourselves when we mistake the unreal for the real; when we believe what isn’t rather than what is.

You are always whole, just as the moon is always full. Your life is always complete. You just don’t see it that way. And until you do, you don’t.

Just let everything and anything be so, as it is, without using any kind of standard by which we make ourselves satisfied, dissatisfied, happy or unhappy. Then you’ll see the plain and clear fact.

A cosmic gift for the season of giving.

Photo by Camille Cox on Unsplash

Empty handed, holding a hoe. —Mahasattva Fu

Empty handed, holding a hoe. —Mahasattva Fu You are the sky. Everything else—it’s just the weather. Pema Chodron

You are the sky. Everything else—it’s just the weather. Pema Chodron