Let me tell you a story about Buddha. This story is often mischaracterized as mythology or parable, because we like to approach things that way. Oh I get it, it’s a fable— rather than facing it as stark reality.

Buddha was born and his parents adored him in that misguided and dangerous way that all parents adore their children. Because daddy was king of the clan, they had the resources to raise their son with considerable advantages. At the same time they had been warned about certain dangers. They had consulted a seer, who said, “Look, your son is either going to be a great warrior king or become a spiritual freak.” So they tried to prevent him from becoming anything other than a king with power and wealth. They didn’t want any damaging influences to detour his ascent to greatness. What spiritual seekers did at that time was . . . weird. They were ascetics. They didn’t eat. They didn’t dress. They didn’t sleep. They didn’t have homes or shelter. The parents had to rule out that nonsense entirely.

Like all of us, they were very afraid that their child would suffer pain or misfortune. So they baby-proofed the house. They put a lock on the toilet lid, the kitchen cabinets and the refrigerator door. They set out to eliminate all hazards, because this is how much they loved their son and feared for his future. As he grew up, he was surrounded by servants to care for his every desire so he didn’t have to go anywhere. And they weren’t just servants. They were the best-looking servants: only young, fit, beautiful people bringing him the finest food, most beautiful music and freshest flowers. Nothing decayed; nothing unpleasant.

I understand a couple of things that are going on here. I understand love, and how as parents we feel the need to protect and control. But I also get what we feel as children. We grow up, and by degree, we keep peeling back the curtain. We’re hungry for the truth. We feel trapped, smothered, and fooled. We know our parents might have good intentions, but after a while all that confinement begins to feel like bad intentions.

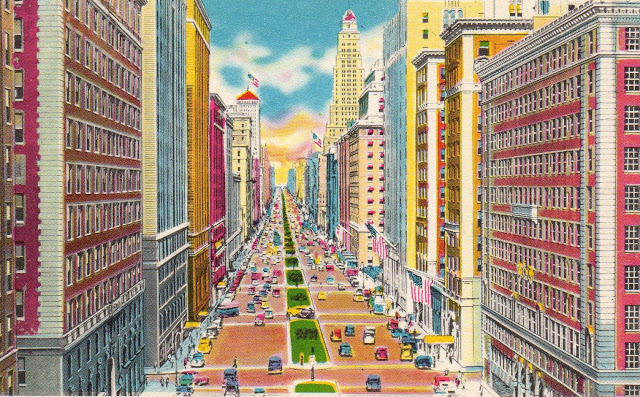

Even though Buddha had everything he ever wanted, he wanted more. He said, “What’s the real world like?” He and his adolescent friends decided they were going do the unthinkable. They jumped over the wall and they went down to the city, that forbidden place. He was gonna have fun!

Only he didn’t have fun. That’s because the first thing he sees is an old person. And he’s like, “Whoa, what happened to him?” Because when you’re 15, you think you’re gonna be 15 forever. When you’re 20, you’re gonna be 20 forever. And then, when you slide over into 30, you think, “Well, at least I’m not 40!”

So Buddha says to his buddy, “What the hell happened there?” And his friend says, “That’s just an old person. We all get old.” That was a downer.

They go on, and pretty soon they see somebody sick on the street. You don’t have to look far to see something like that no matter where you live. Even now when you see it, do you really see it? Nowadays if you get sick, what’s the first thing you think about? Prevention. “If only I’d . . . worn a mask on the airplane . . . hadn’t eaten sushi . . . gotten a flu shot . . . taken a different elevator.” What we’re always trying to do is engineer a different outcome: perfect health, happiness, and the fountain of youth.

A whole lot of what we buy feeds into that delusion. You’re not going to get sick if you use this. You’re not going to get wrinkles. You’re not going to get gray hair. You’re not gonna get old. What’s implied in everything we buy is you’re not going to die. Because the same night Buddha sees the old guy and the sick guy, he sees a dead guy.

Old age, sickness, and death. That’s reality, not a myth.

So what does Buddha do when he comes away dazed and confused from the most shocking night of his young life? He looks around at the hordes of people – his friends, his family, the crowds milling around town, buying and selling crap — and says, “How can you live like this? If you know you’re going to get old, sick and die, why do you live as if it’s not going to happen?”

He’d been born into brocade and jewels. He’d come from a palace. And he saw what it wasn’t. It wasn’t real. It wasn’t true. He realized that he needed to relinquish his false identity of privilege and immunity. He needed to get comfortable with the uncomfortable, irrefutable and irreversible truth that we grow old, we get sick and we die.

Right then, he dedicated himself to resolving this dilemma: How can we live if it’s for nothing? What do we do and where do we go, if there’s no way out?

“This is where we start,” he said, and sat down to see it through.

Excerpted from a Dharma Talk, “The Truth of Your Life” which you can listen to via this link.

***

Photo by Henley Design Studio from Pexels